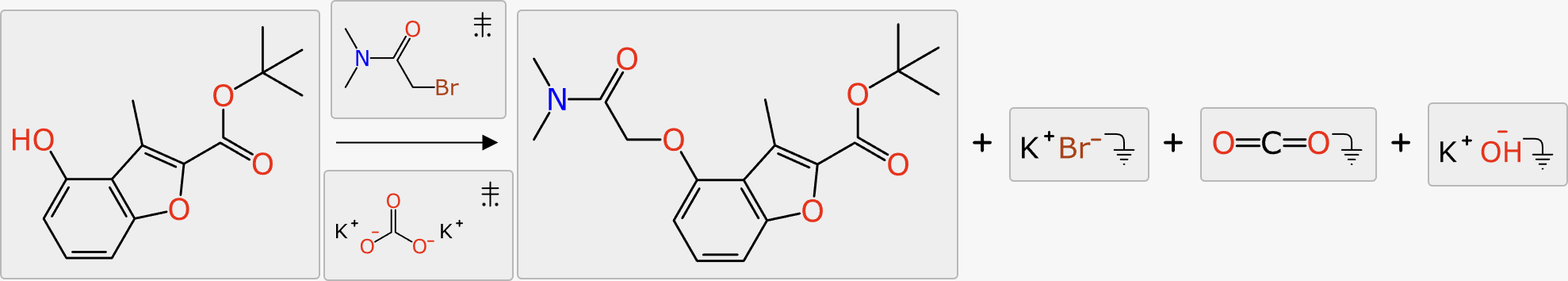

The process of completing a reaction scheme includes four preliminary co-dependent steps: proposing formal byproducts, obtaining pairwise atom-to-atom mappings, balancing the stoichiometry, and assigning roles to each of the reaction components.

This is a series of articles about reaction prediction. The summary overview and table of contents can be found here. The website that provides this functionality is currently in a closed beta, but if you are interested in trying it out, just send an email to alex.clark@hey.com and introduce yourself.

These four steps are described in a single article, even though each one has its own distinct methdology, because they are executed as a group: iteratively when necessary. They also occur chronologically before the previous articles: catalysts and solvents can only be predicted once these preconditions have been met.

- byproducts: while some reactions have a single product that formally consumes all of the input atoms, most have at least one additional molecular entity that is not part of the desired outcome (e.g. eliminating a water molecule); ensuring that these are present and correct is useful for reaction planning, and also necessary to determine when a reaction is balanced

- stoichiometry: each of the reactants, reagents, products and byproducts has a coefficient which indicates how many molecular equivalents are involved in the reaction; while the default value of 1 for each component is correct for perhaps the majority of organic reactions, determining the multiplicities is the core activity of reaction balancing

- atom mapping: every atom in the reaction input collection (reactants and reagents) must be mapped to exactly one atom in the reaction output collection (products and byproducts), taking into account stoichiometry

- roles: for purposes of this block of functionality, the need to know is whether each of the components above or below the arrow is a stoichiometric reagent which participates in the mapping and balancing, or whether it is a spectator of some sort that does not contribute atoms to the product

Each of these four goals requires a significant amount of modelling and/or algorithm complexity on its own, but the overall objective is much more challenging due to the fact that decisions about any of them feed into each other. For example, byproducts must be known in order to evaluate whether reaction balancing is complete. Atom mapping can’t be complete until the stoichiometry is correct. When component roles are unspecified, deciding whether to map an atom of an agent to a propoposed byproduct can change a component from a spectator role to stoichiometric reagent, which alters all of the other processes.

The algorithms are run within a loop, which frequently only needs to execute once, but in some cases needs a couple of laps around the track.

Byproducts

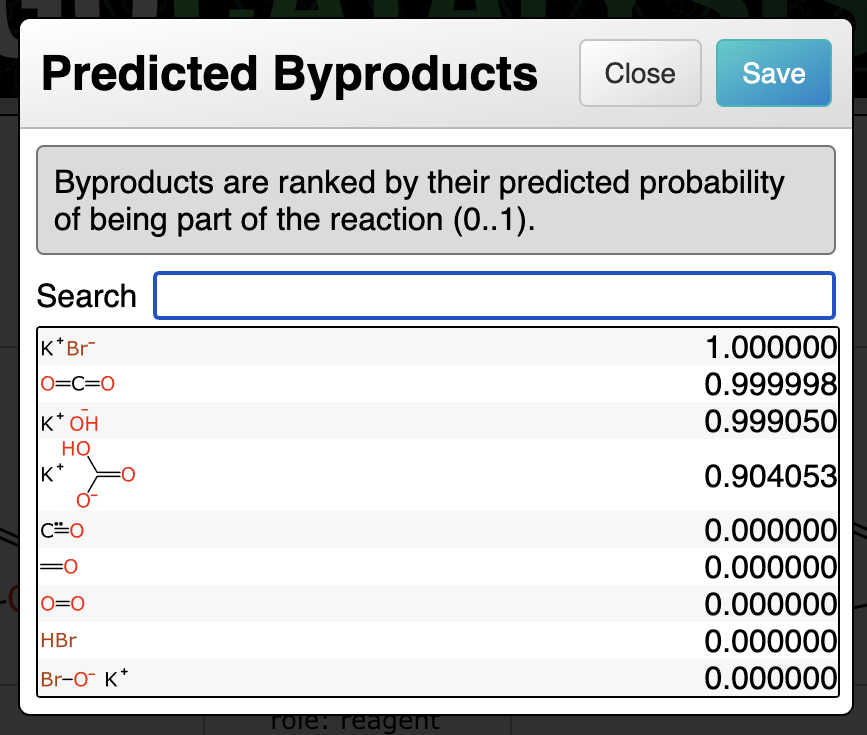

Prediction of byproducts uses a graph-based deep learning model that is similar to the catalyst and solvent models, with the inputs being labelled graphs of the reaction transform and the proposed byproduct. The output is a simple probability: for the training data, a given structure either is or isn’t a byproduct of the reaction.

For deciding which byproducts to propose and rank, the total atom balance of the reaction is added up. Any of the byproducts that has been observed in the training data is considered fair game if there are sufficient leftover atoms to assemble it.

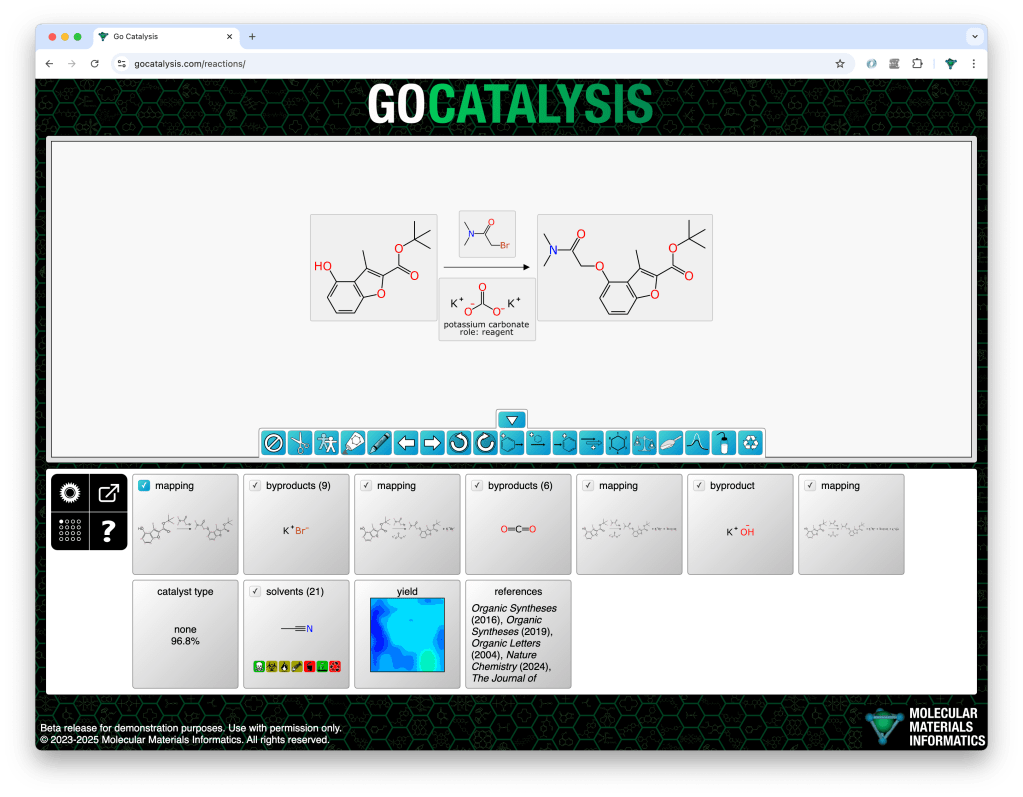

In the following example, the decomposition of potassium carbonate produces three byproducts in succession, and each of these is proposed and ranked sequentially:

Mapping

Prediction of atom-to-atom mappings also uses a graph-based deep learning model, but this one works a bit differently: the graphs are reused multiple times, as pairwise combinations of reactant and product atoms (as long as the element is the same). For generating training data, the atoms either are mapped or they’re not (with redundancy due to symmetry taken into account). The model is able to predict the likelihood that any two atoms are mapped, in context of the whole transform (including byproducts).

Having a list of pairwise prediction is not the end of the matter though. Atom mapping is a zero tolerance model: you get one atom pair wrong and the entire reaction interpretation falls apart – the transform is nonsense, and it goes downhill from there. The post-processing assignment is somewhat greedy, meaning that it starts with the most certain predictions, and builds out the atom assignment with a bit of procedural logic to discourage the occasional model glitch from breaking the whole process.

Note that one of the jobs that the mapping model has is to be able to tell when entire components are off limits. Reactions often contain a number of components above/below the arrow, and some of these are reagents which should be mapped to products and byproducts, and others are catalysts, solvents or adjuncts which should be left alone. These bystander components are sometimes marked explicitly, but usually they are not, and so the mapping model has to be fed enough training data to be able to make an educated guess. When a spectator component is assigned an atom match for the first time, it switches status and becomes a reagent, which means that it now factors into the stoichiometry and byproduct prediction processes.

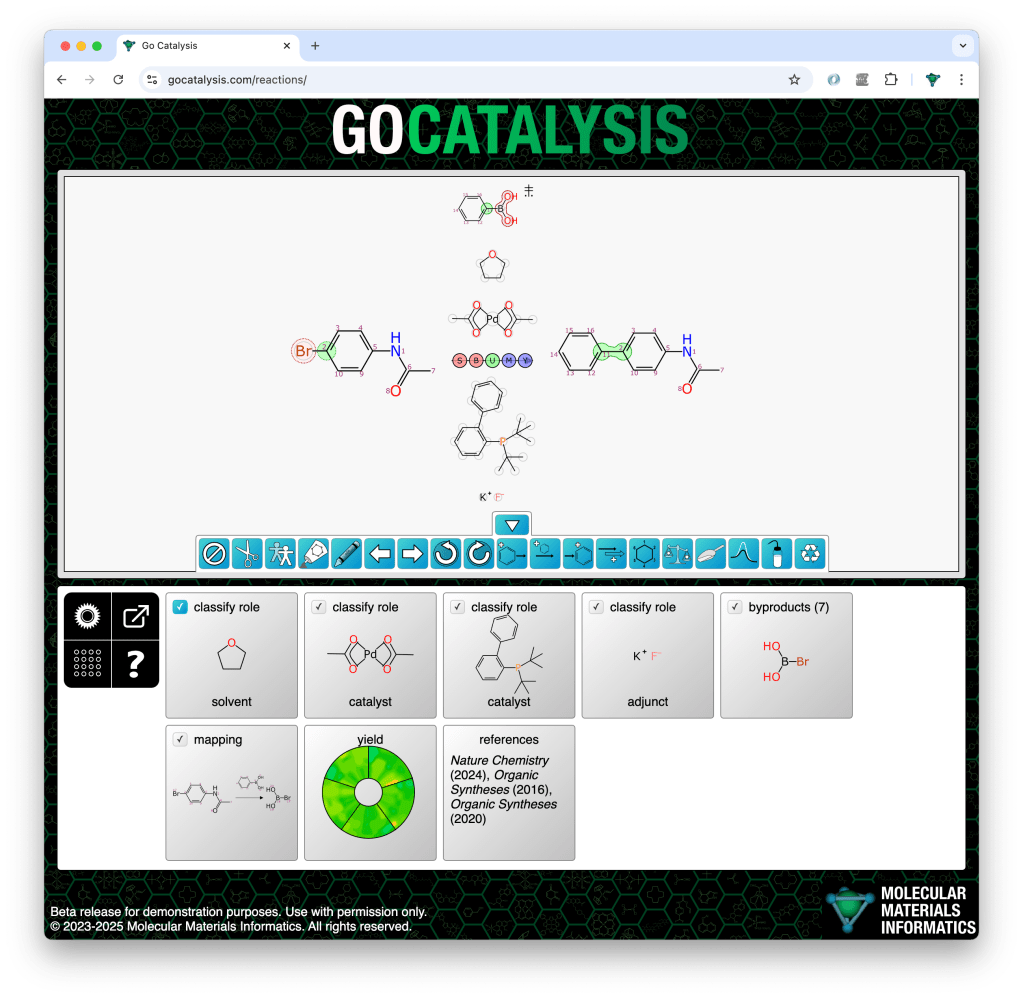

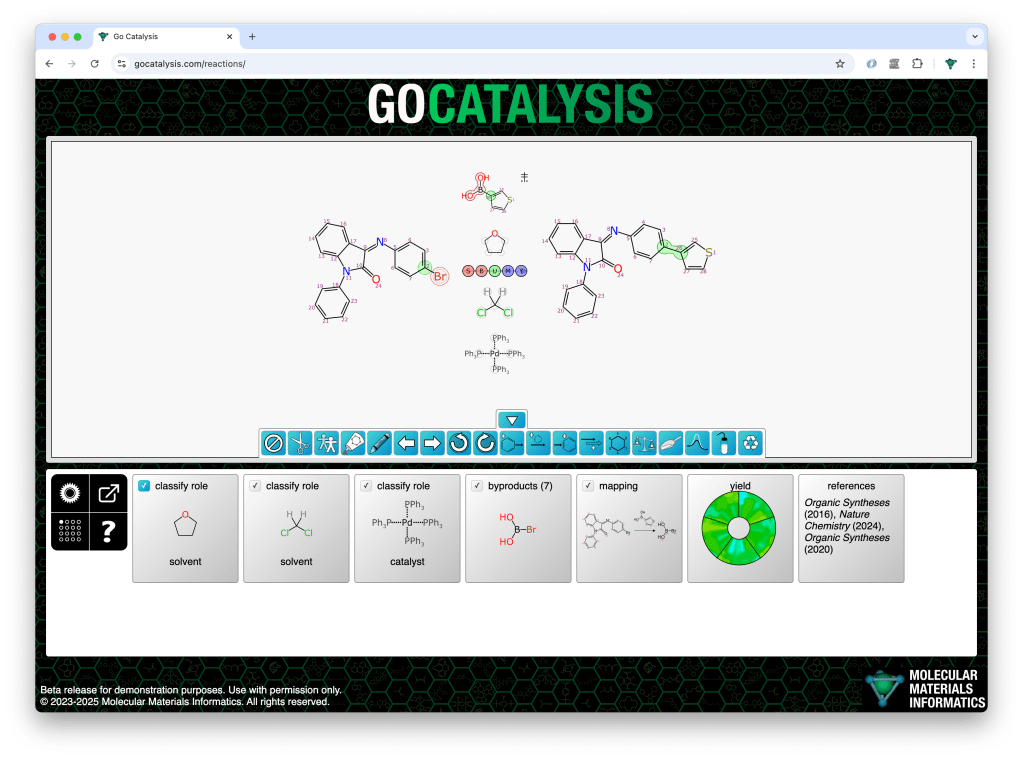

In the following example, the prediction starting point is one starting material, one product, and 4 components above/below the arrow. As a chemist I know that the top one is a reagent, the middle two are solvents, and the bottom one is a catalyst. But the model doesn’t know that… or does it?

Note that of these four middle components, only the reagent has been mapped to the product. The other three have been left alone.

Balancing

At any stage in the iteration it may be possible to make the overall atom excess/deficit shrink or go away by tweaking the stoichiometry coefficients for both sides of the reaction. The algorithm is not especially sophisticated because reactions rarely have more than half a dozen stoichiometric components, and equivalents can be factored out to become whole numbers, which are usually 1, often 2, occasionally 3, and rarely more than that. This combinatorial explosion is generally more of a fizz.

The main pitfall with reaction balancing is that the byproducts and role classifications are not known ahead of time, so prematurely dialling up the equivalents of a component can seem like a good idea, given what is currently known, but actually make a mess. Other times it’s necessary to increase a coefficient in order to facilitate the allowance of a byproduct (which is disallowed from using more atoms than are available).

Balancing is made slightly more awkward by the early decision to limit the explicit setting of stoichiometry to reactants and products/byproducts, but not the reagents (which are drawn above/below the arrow). Reagent stoichiometry is calculated by using the atom mapping to factor out the equivalence from the product atoms each is connected to.

Roles

A single step reaction is divided up into 3 main sections: reactants are on the left, products and byproducts are on the right, and all the other stuff is drawn above/below the arrow. Because of the conventions used by chemists, and the need to use a component-based datastructure that is suitable for multistep reactions, the arrow region includes a variety of different roles, which include reagent, catalyst, solvent and adjunct. These roles can be marked explicitly, but typically they are not.

An arrow-region component becomes definitively classified as a reagent the moment one of its atoms is mapped to an atom on the right hand side of the reaction: it is now known to be stoichiometric, because it contributes atoms to the product. The non-stoichiometric roles are all equivalent for this calculation loop, because for these purposes, it’s either a reagent or it stays out of the way.

The next article in the series describes automatic literature lookup.