Sometimes the best way to validate a prediction is to go check the literature and look for the most similar examples, to see if it looks reasonable. Fortunately the data that these reaction prediction tools are based only mostly comes with a DOI attached, so this feature can be added automagically.

This is a series of articles about reaction prediction. The summary overview and table of contents can be found here. The website that provides this functionality is currently in a closed beta, but if you are interested in trying it out, just send an email to alex.clark@hey.com and introduce yourself.

Explaining why a neural network model made a certain prediction is generally somewhat of a challenge. The literal answer is because when we multiply these matrices together in this order, it provides the best overall correspondence between predicted and observed. The reason why a particular prediction scored particularly high or low is so heavily obfuscated that it has to be treated like a black box. One way to help out with this situation is to develop a confidence metric, but that requires a second leap of faith.

In the series so far there have been several mentions of the training data, and that it is made up of very carefully curated reactions that are considered scheme-complete, i.e. all structures are present and tagged with roles, and stoichiometric components are mapped and balanced. These and several other criteria are used as a hard requirement for being allowed into the model building pipeline.

Since most of the input data is curated from literature articles, the curation documents have been marked with the DOI (digital object identifier), which is another way of saying that we have a link to the published article. So if we can find the training data examples that are most relevant to a prediction, then presenting those as links is an effective way of finding a likely explanation for the basis of a prediction. And even if reading the article convinces you that the prediction was not so great, it is likely to be relevant, so it’s a decent consolation prize.

Finding a literature reference involves generating fingerprints for graphjs of interest:

- transform fingerprints for the stoichiometric components

- structure fingerprints for catalysts and solvents

Comparisons can be done simply using the popular Tanimoto metric, and focusing on the different categories as appropriate. There are three places in which literature comparisons appear in the interface. Results are only shown when there is a DOI-containing entry with a minimum threshold similarity, so there is sometimes nothing to show.

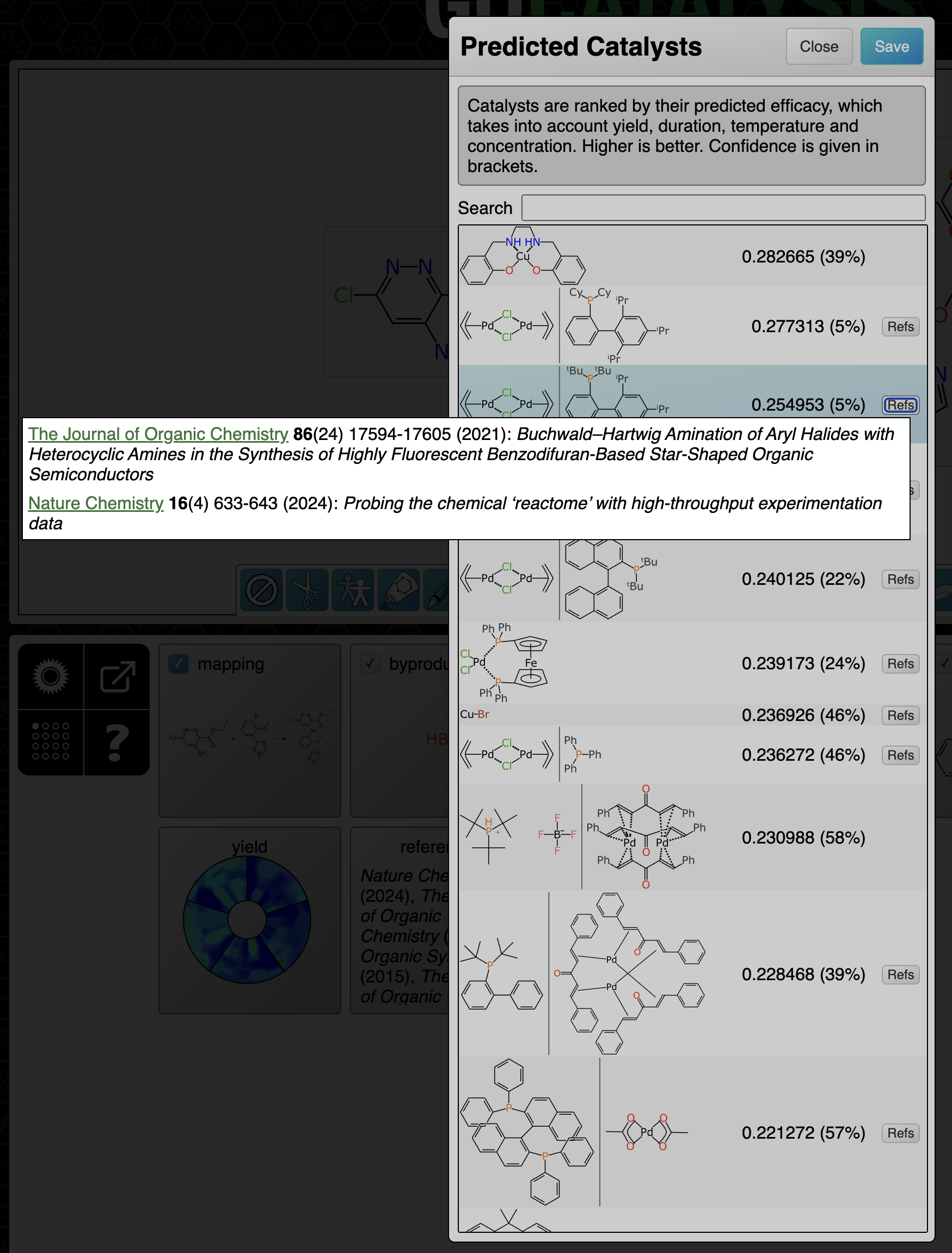

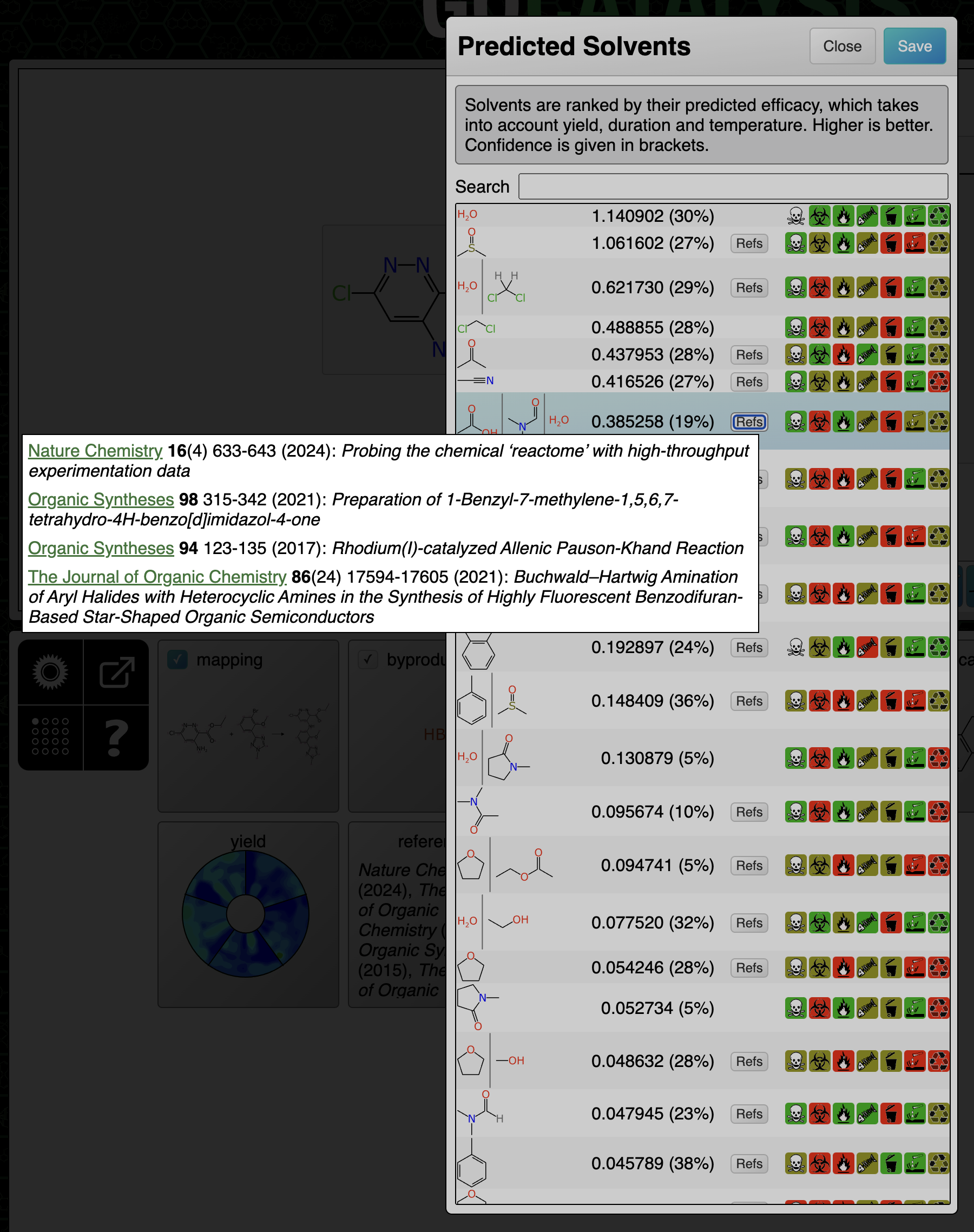

Catalysts and solvents: references are composed and ranked with the catalyst/solvent similarity being the primary factor, and similarity of the transform being secondary. Because only reactions with the same core transform are considered, this is effectively measuring how similar the substituents are.

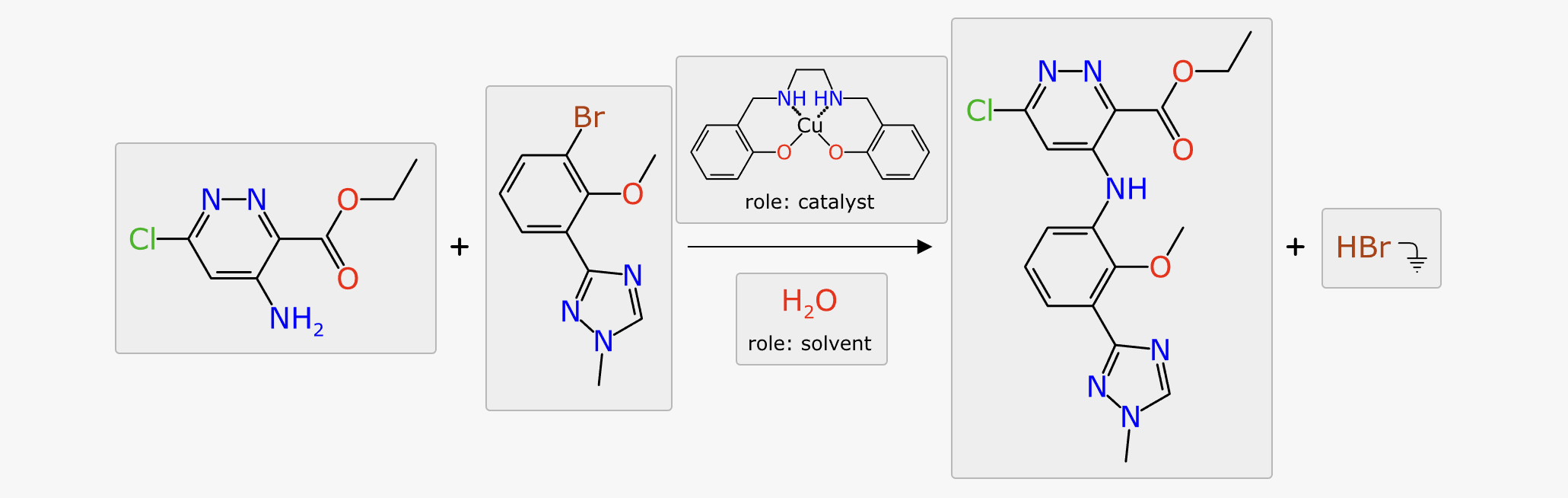

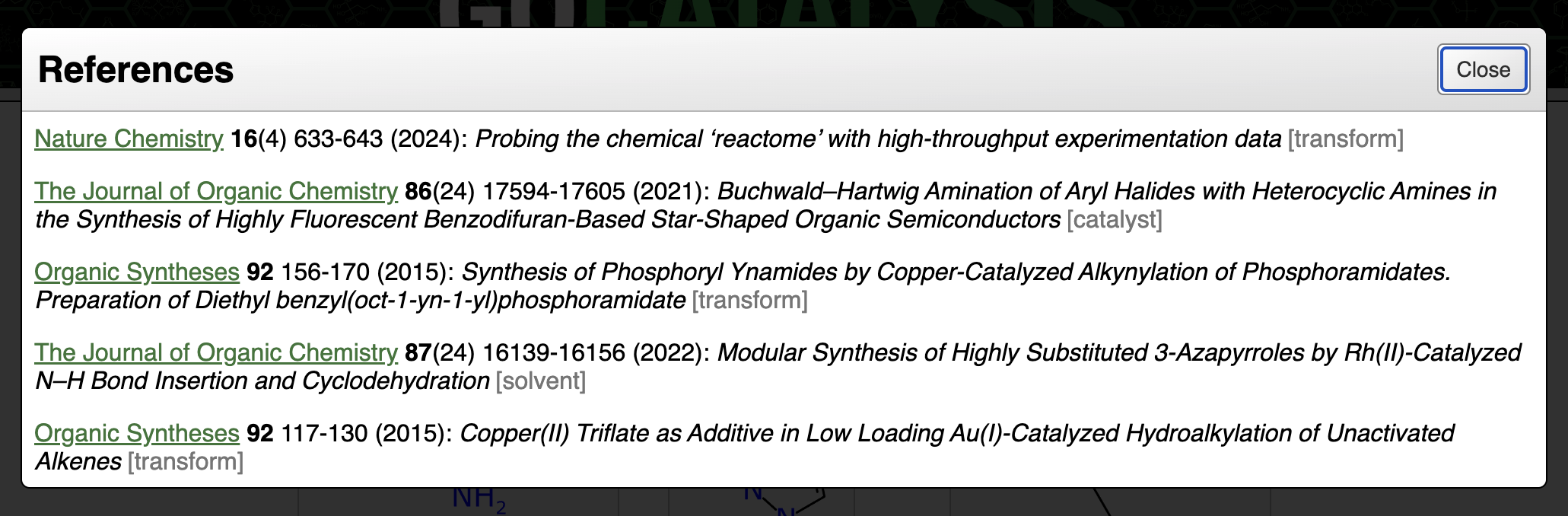

At the end of the prediction sequence, the hypothetical reaction that would’ve been composed if all of the top ranked suggestions were applied, is compared to everything in the training data. The results are divided up based on the attribute that was found to be most similar, e.g. because of similar catalyst, similar solvent or similar transform:

This functionality is very useful for deriving a justfiable rationale from a prediction, on a case by case basis. Most of the references are to articles that describe a series of reactions, but they do tend to be closely related, especially for catalyst method papers, so the theme is usually applicable to the task at hand. It can also be useful for just doing a direct reaction lookup, although the total amount of data behind the scenes is a tiny fraction of the overall literature.

The next article in the series describes yield contours.