Using models to propose recommendations for chemical reactions is appropriate for many of the steps needed to fill out the scheme, but sometimes it’s more effective to pick an existing reaction and use it as a template to build out the missing pieces. This approach can be applied to forward and backward syntheses (starting from a reactant or product respectively) and also to finding and proposing stoichiometric reagents.

This is a series of articles about reaction prediction. The summary overview and table of contents can be found here. The website that provides this functionality is currently in a closed beta, but if you are interested in trying it out, just send an email to alex.clark@hey.com and introduce yourself.

Anyone who has ventured down the rabbithole of software-driven retrosynthesis is familiar with the strategy of pre-curating a number of reaction transformations that can generate a synthon (B ⇒ A). By applying these transforms to a growing tree of reactions, as long as it is pruned effectively to avoid combinatorial explosion, it can be used for reaction planning. There are a number of commercially successful products based around this strategy.

The algorithms described in this article are related, but approach the problem differently. Each and every reaction in the training set is an exemplar that is fully marked up: for the task at hand, it is only necessary for all of the stoichiometric components to be present, which includes reactants, reagents, products and byproducts, and they must be mapped and balanced down to the last atom.

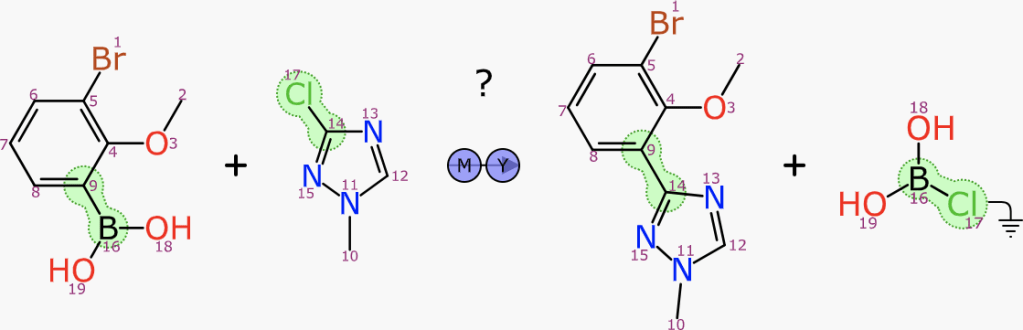

In previous articles we have alluded to the idea of the core transform, which is any atom that changes its local environment when going from the left hand side to the right hand side:

The highlighted atoms make up the core transform, and everything else is some number of steps away from it in graph distance.

If the user input consists of just a product, and nothing else, we can consider this as a request to search for backward syntheses: each reaction in the training set is an exemplar, and it might be possible to adapt it to fit the structure of the target product. This implies a rather large amount of work, which proceeds as follows.

Extract the core transform from the exemplar, and initially just use the atoms that originate from the product (excluding byproducts). Perform a substructure search of the product core within the provided target molecule. The product core graph is usually quite small, sometimes just one atom, so there can be a lot of matches.

For each substructure hit, the ensuing sequence is followed. Each of the product core atoms can be traced back through the exemplar to a reactant core atom, and these are placed within the initial starting point for the reaction proposal. From there, the task is to successively grow the proposed reaction scheme:

- some number of atoms in the target product have been assigned to a corresponding atom on the reactant side: consider all target atoms that are directly connected to this subset

- resolve symmetry where necessary: the trick is to apply a metric that encourages the walk path to map target product atoms that are in maximally similar environments to the exemplar template reference

- for each of these selected neighbour atoms, surgically augment that reactant side, adding in the element from the product, giving it the same new atom-to-atom mapping number, as well as reproducing its bonds any previously matched up atoms

- continue until none left

Note that all of the atoms that are built during this iteration process are by definition not part of the transform, meaning that their bonding environment is the same on both the product and reactant sides.

These steps gloss over a lot of details. The symmetry tiebreaking involves an adapted version of structural fingerprints, which project outward from a reference point. Creating new atoms borrowed from one side and added to the other is best done with mindfulness of coordinates, because even with subsequent redepiction, randomising stereochemistry is not good. Most reaction transforms are spread across multiple components (e.g. starting material + reagent) which raises issues of its own, including special logic for connected components (such as salts) that are not formally involved in the reaction.

Once all of these algorithm details are worked out, the result is a partial reaction description which contains all of the stoichiometric reactants and the main product, adapted from the exemplar reaction scheme to match the provided product. The atom mapping is maintained throughout the procedure, so that comes along for the ride. The partial reaction can then be subjected to an aligned depiction (described in the next article) in order to get the aesthetics right.

Outside of the specific implementation of the fabrication process, the algorithm does often produce a lot of results, especially when the core transform is not very specific. Many of these are duplicates, and so a reaction isomorphism detection algorithm is needed: this is implemented as a variation of the substructure search, with various optimisations that are specific to isomorphisms, which operates on pairs of atoms (left & right) rather than individual atoms.

After elimination of numerous duplicates, the remaining issue is that most inputs do generate quite a lot of reactions that are rather silly. Just because a transform core matches, doesn’t mean the chemistry works. Considering the analogy to retrosynthesis algorithms that use pre-curated transformations, those are generally constructed ahead of time to eliminate chemistry that isn’t sensible. The method described above leaves that step to the end. At the time of writing (April 2025) the tool does not do very much filtering, but instead chooses to rank the proposals according to how closely they resemble a real example.

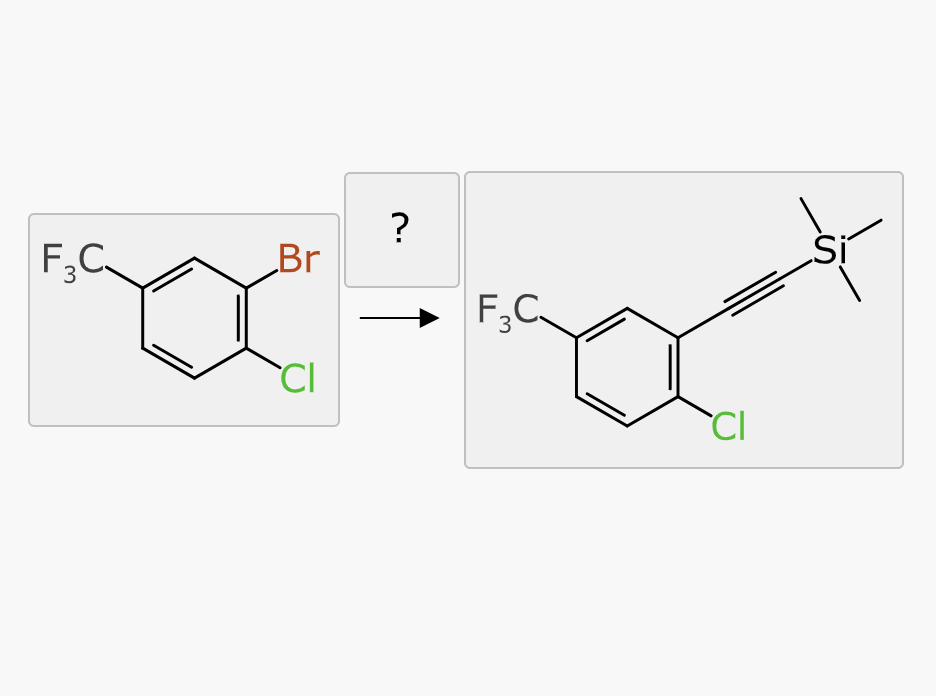

The steps described above are equally applicable to the reverse direction, i.e. the user provides the structure of a reactant, and wonders what reactions might be subjected to it. This is not as relevant to synthesis planning, but there are plenty of scenarios where it is a useful question to ask.

Another difference between using exemplar reactions as templates vs. precurated transforms is that this method is a lot more labour intensive. But it does have some key advantages, assuming the filtering and ranking can be improved: the newly constructed reactions are balanced and mapped and aesthetically ready for viewing out of the box. It is also purely data driven: there is no extra step to decide whether a transformation can or should be applied to a proposed target. In comparison to transforms that are precurated manually by experts, this has the advantage of being able to greenlight transformations that were not anticipated by the curator – at the expense of transferring a greater burden onto the filtering algorithm, due to the more frequent generation of non-viable options.

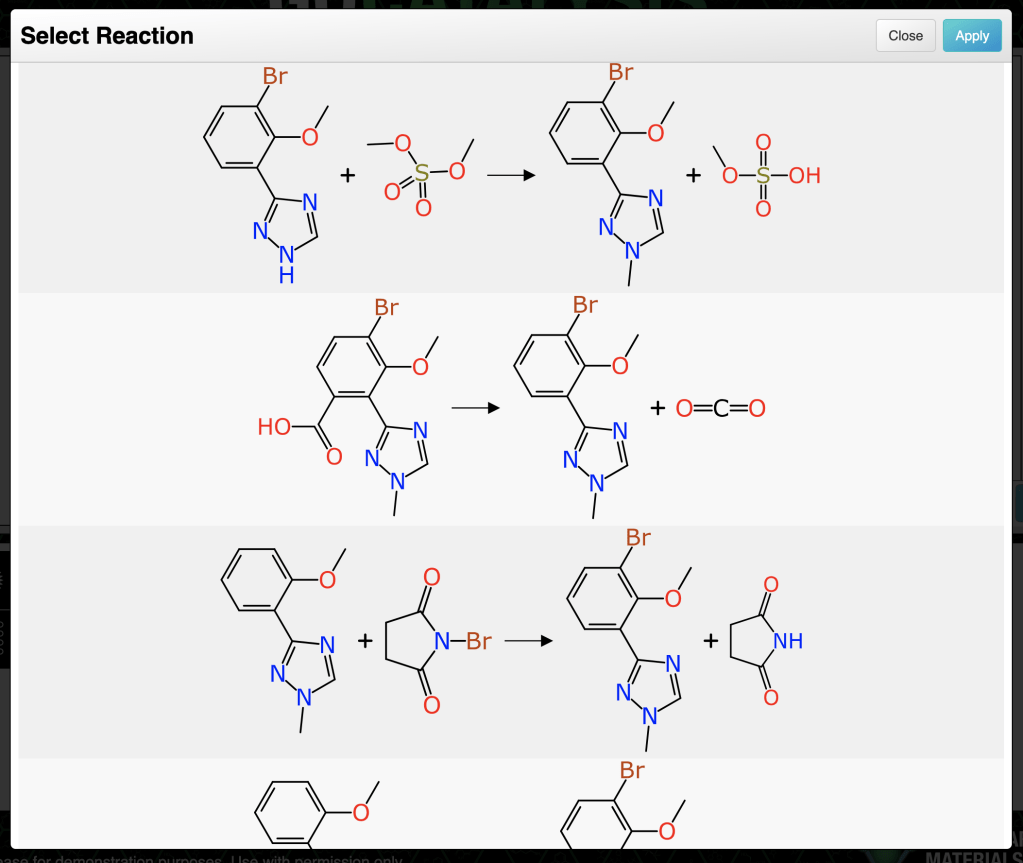

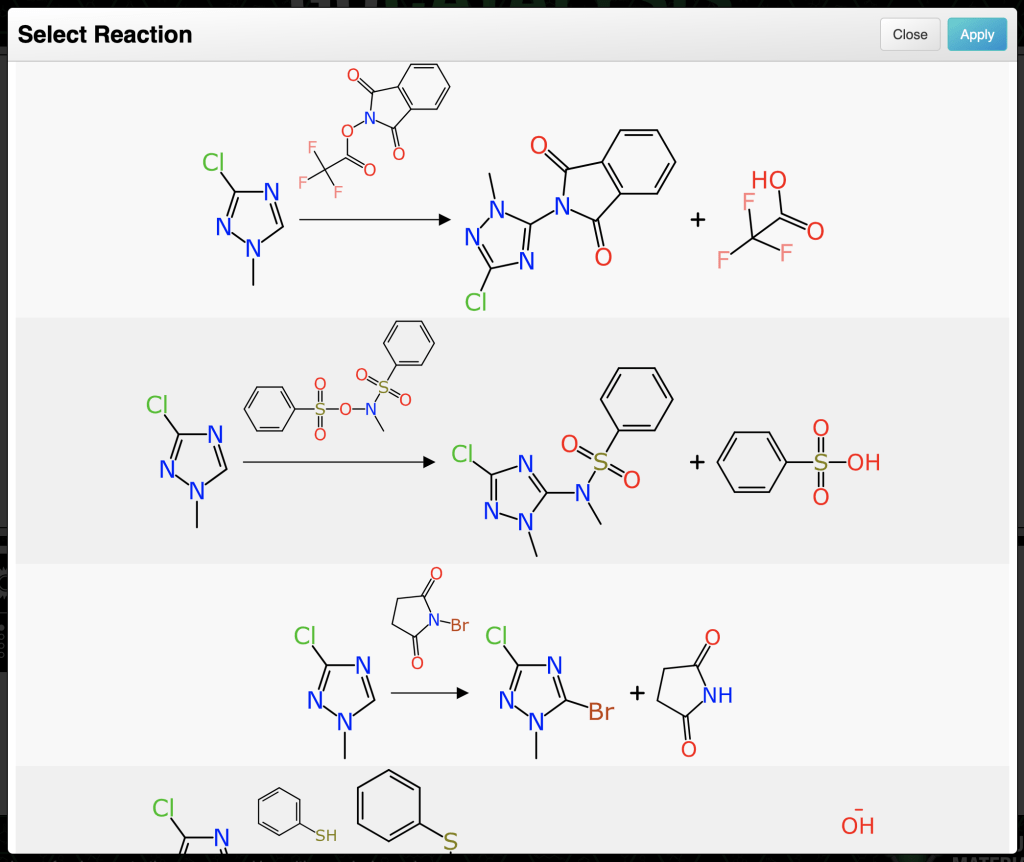

There is another related algorithm that kicks in when the user has provided something in the reactant and product regions: searching for stoichiometric reagents. The algorithm works better when some of the reactant/product atoms have been mapped, although it also works when they are not.

The transform substructure search is related to the forward/backward synthesis algorithm, but this time it is searching on both sides simultaneously. The transform core is limited so that reagent and byproduct atoms are both left out of the query. A specialisation of the substructure search is used to achieve this with reasonable efficiency.

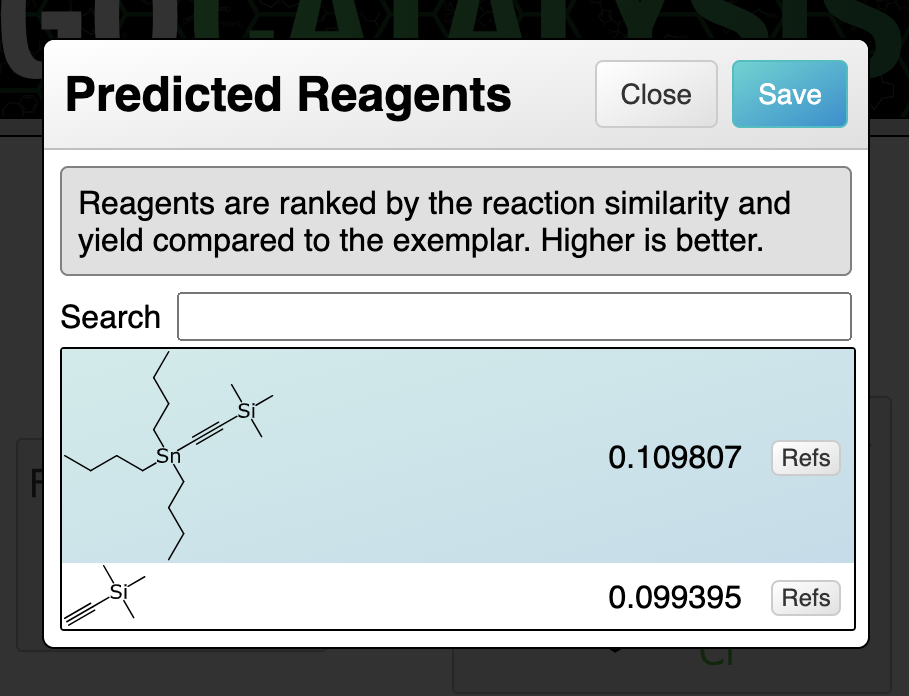

The transform query will necessarily include at least one product atom that has no corresponding reactant atom, because in the exemplar reaction, its pair was assigned to the reagent, which was explicitly left out of the query. For each hit that is established, these dangling mapping references are traced to the reagent from the exemplar reaction, which is then considered as a reagent candidate. The process involves finding the mapping to the product (as well as performing an implicit mapping operation if not already present, or using existing mapping as a filter if it was).

The resulting reagent proposals are deduplicated using a full reaction isomorphism test, which operates correctly whether some or all of the atoms are mapped. It is possible that a reagent can be applied in two different ways, so results could include the same reagent more than once.

The reagent is also subjected to an aligned depiction, in order to get a reasonable orientation.

At a glance it may seem inconsistent to use an algorithmic method for selecting reagents, whereas catalysts and solvents are model-based. In actual fact this complex algorithm is really just the pre-filtering method for selecting potential reagents. Catalysts and solvents have their own pre-filtering method, but it is a bit more straightforward. Because the filtering method for reagents is so selective, most of the value is concentrated there. A ranking model for deciding which reagent would work best basically just uses the yields from the matched exemplar reactions to provide a reasonable ordering, which is good enough for now, given that there are usually only a handful of results.

The next article as about depiction alignment.