There are two main approaches to drawing reactions: the canvas model, where everything is drawn onto a flat page, and the component model, where each reaction participant is treated as a discrete object. Both of these approaches have important advantages, and significant problems which have to be addressed.

This is a series of articles about reaction prediction. The summary overview and table of contents can be found here. The website that provides this functionality is currently in a closed beta, but if you are interested in trying it out, just send an email to alex.clark@hey.com and introduce yourself.

The canvas model for reactions is driven by the very real need to prepare reaction diagrams for publication. It was a little bit before my time, but apparently professional chemists used to own physical stencils for preparing manuscripts. When tools like ChemDraw appeared on the scene in the 1980s they swept chemists off their feet, because the value they provided was so incredibly high. As is often the case, the success history of a product category can also be a liability: in this case the strong emphasis on empowering chemists to get the aesthetics exactly to their pleasing does not fully track with the internal meaning of the datastructure. To a practicing chemist, the implicit working assumption is that because the diagram looks right and is interpretable to another chemist, and it’s on a computer, therefore it is digitised. Even though most people in the industry know that this isn’t quite true, the finer details are something that only a few of us really lose much sleep over.

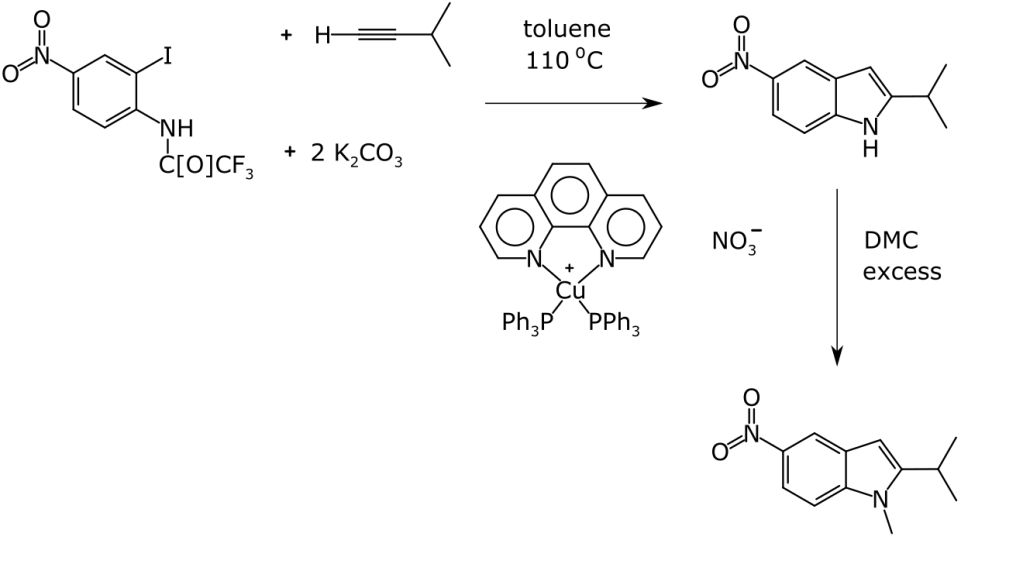

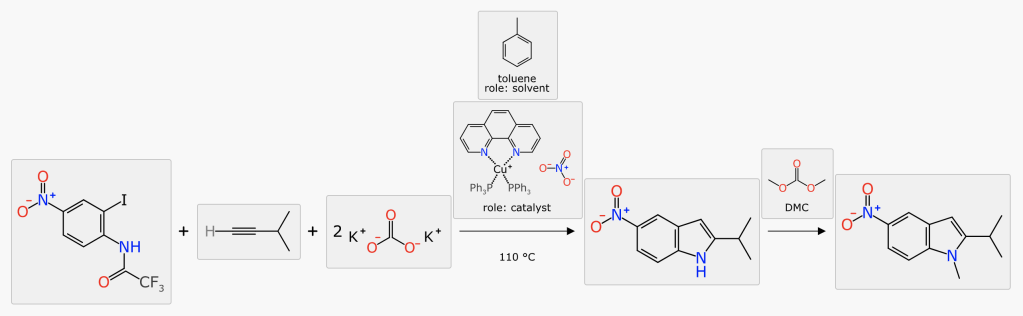

An example of a reasonably well drawn reaction is this diagram that I prepared some years ago for a presentation, to use as a counter example:

For human communication, this is fairly clear. In the absence of any underlying cheminformatics metadata, all the computer sees is the jumble of shapes shown on the right, with some potentially relevant positional information. Unless you have converted your figure into a PDF, you probably do have at least the basic atom and bond connectivity from the underlying drawing. Even with the basic connection table available there are still a lot of interpretation challenges, if you want to spend some time playing spot-the-problems (there are quite a few).

An algorithm (whether it be in the drawing package or the following interpretation) has to figure out:

- the distinction between reaction components and connected components

- assignment of each component as a reactant, product, or agent relative to arrows and pluses

- interpretation of text, which can indicate stoichiometry, conditions, notes, or some creative way to indicate state

- undefined abbreviations drawn in as text, or whole components indicated using mnemonic shorthand (e.g. “THF”)

- use of shapes to visually indicate chemistry, e.g. multicoordinate bonds

- multistep reactions or large molecules wrapping around the page or spilling over the boundary

The other reaction representation strategy – the component model – is the option that prioritises informatics, and sidesteps most of these issues. The reaction is described as a list of objects, each of which has a number of properties, some of which may be mandatory depending on the use case:

- chemical structure (with atom mapping)

- stoichiometry

- position in reaction (reactant, product, above/below arrow, step)

- role clarification (limiting reactant, stoichiometric reagent, solvent, catalyst, adjunct, byproduct, etc.)

- quantity (various measurement types)

- name

The catch is that component-based reactions are designed to be easy to manipulate procedurally, which means you can add, delete or move objects around just by operating on the list. The coordinates of each of the chemical structures for each of the components are relative only to themselves, not the overall canvas. There is also no need for decorations like the reaction arrow, and the chemical structures tend to be drawn using CTAB-like datastructures, meaning that there are not very many aesthetic customisation options. Getting a reaction ready for a chemist to view requires a special layout algorithm, and the presentation is what it is: there are no convenient options for moving things around to get it all just the way you want it.

The reaction layout algorithm described in this series works something like this:

- if there is a box boundary to try to fit into, try several variations on horizontal/vertical arrows for each reaction step, and placement of reactants/products left-to-right or on top of each other

- for each component, find an outline box that fits the structure and any metadata that has been requested (e.g. display of names or quantities may be optional)

- for each region (reactants/arrow/products/multistep) determine a bounding box, made up of the sizes of the components, the plus symbols, the reaction arrow(s), and appropriate spacing

- for components above/below the arrow (or left/right if vertical) split them into two equitable sizes

While the diagrams that are produced by this method are of high quality, it is generally possible to tell that they weren’t drawn with loving care using a dedicated drawing tool for a high value publication. But it’s usually pretty close.

There’s another important consideration: drawing out reactions using a canvas-based editor is rather painful. Creating just one or two for a high impact presentation is fine, but when it’s more than a few, all of that clicking and dragging to move the components to the right places and line them up with the arrows and scaling them to fit and scrolling past the page when it gets big – it adds up to a lot of time for surprisingly simple-seeming tasks. One is naturally given to thinking that it would be nice if the software could just take care of the meta layout: just let me provide the molecules (either by quickly drawing them, or finding them from elsewhere) and sort out the rest of it without any hassle.

That’s basically what a good reaction component editor does. In particular, it should:

- allow components to be provided in any order

- automatically arrange the reaction in a chemist-friendly display

- embed a single molecule sketcher

- make generous use of cut’n’paste

- provide lookup lists for common chemicals

- analyse the reaction to provide feedback about completion status and mistakes

- provide reaction-specific functionality like manual/automatic atom mapping and aligned depiction

These features are implemented on the gocatalysis.com site, as a single reaction editing interface. The component editing functionality meshes in with the handoff to all of the prediction machinery, which uses heavyweight models and algorithms to try to work out facts about the reaction that have yet to be provided, as well as make predictions for how the reaction could be done.

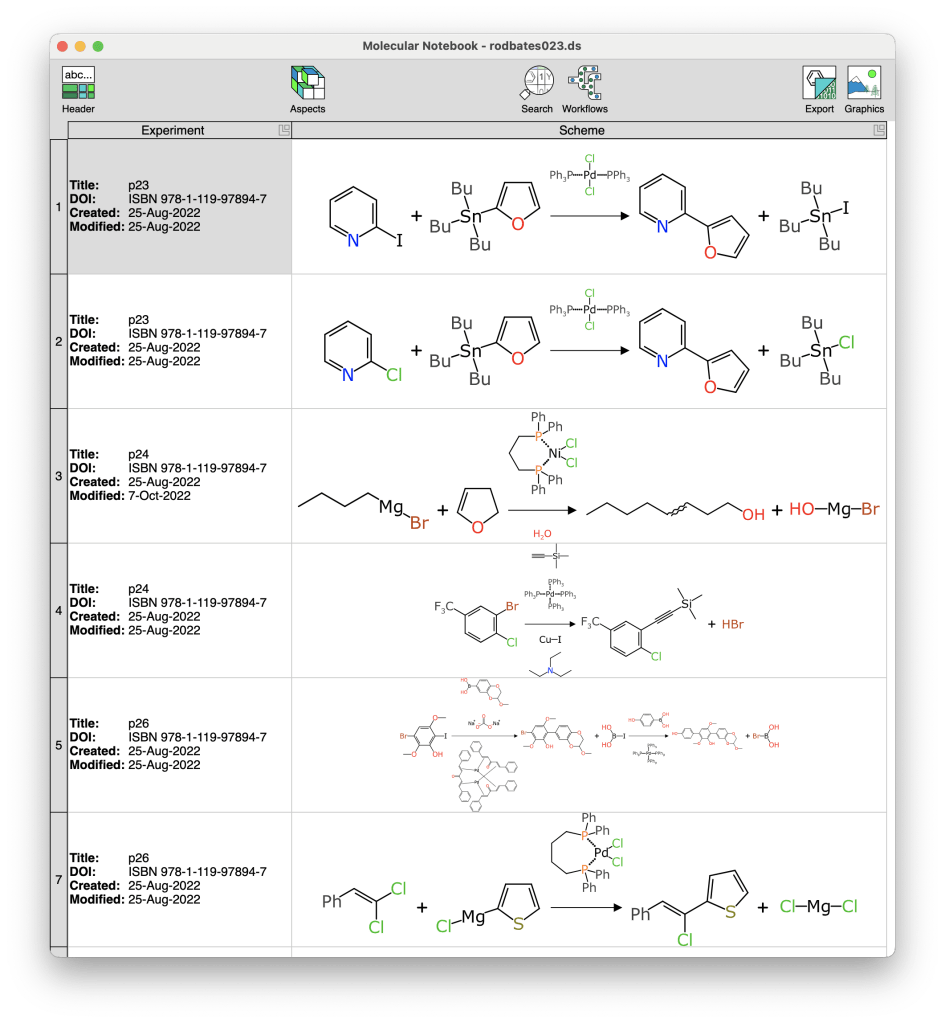

You can try out the reaction editor online, but there’s a variant of it that is optimised for curation of series of reactions in a single sitting. The tool is called Molecular Notebook, and was originally prototyped as an Apple-only interface, but I eventually migrated it over to using the Electron framework (web runtime on the desktop, basically). This is used internally only, so at the present time there is no way that you can have it, but it has the distinction of having been used to curate thousands of reactions from the literature.

Every time you spend an evening transcribing a scientific papers into high value digital content, you invariably come up with a laundry list of ideas about which repetitive tasks are wasting the most time, and how they ought to be made much easier. The most annoying tasks bubble up to the top of the list, and eventually get dealt with.

Two of the biggest pain points for curation are: (1) creating several dozen reactions that are mostly the same, with small differences; and (2) making mistakes. A lot of reduction in repetition can be alleviated by clipboard use, but there are some more creative options as well, like defining columns of variables (scalar properties or R-groups) that are automatically applied to a reaction template. Mistakes are anathema to the use cases that I have for the data that I’ve been creating, and there are a lot of ways an algorithm can help. Obvious problems can be visually flagged, such as missing or invalid yields; unmapped or badly mapped atoms; or an overall atom imbalance.

The next article in the series describes the training data.