There are a number of capable synthesis planning tools available to chemists. A retrosynthesis algorithm usually returns the barebones reactant/product pair for each step, which leaves plenty of work to do before the experiment is ready for the lab. Reaction prediction tools can help get these suggestions closer to a proposed experiment.

This is a series of articles about reaction prediction. The summary overview and table of contents can be found here. The website that provides this functionality is currently in a closed beta, but if you are interested in trying it out, just send an email to alex.clark@hey.com and introduce yourself.

Synthesis planning is usually implemented by gathering a collection of retrosynthetic rules, each of which consists of substructure matching queries to find the transform within the product, and build out corresponding reactant(s). A retrosynthesis step is written as B ⇒ A, where B is the product. The sequence is written in the opposite order to a reaction, because a synthetic chemist is working backwards, starting with the final product and breaking it up into stepwise procedures.

For implementation purposes, the retrosynthetic rules are usually encoded as ReactionSMILES/SMIRKS, or some equivalent technology that can be quickly matched to a final (or intermediate) product and emit one or several ingredients. For any given target molecule there are often many rules which could match, so the overall process generates a large tree of possibilities, which must be ranked and trimmed down to create a plausible strategy, which ideally starts from commercially available inputs. The final outcome may be a linear sequence, or a tree (convergent synthesis), or sometimes just a single step.

The single step rule application of B ⇒ A implies a reaction of A ➝ B, to which needs to be added some number of reagents, catalysts, solvents, adjuncts, byproducts and conditions. Generally the reactants and products are not mapped, and they are usually not drawn in a way that shows common alignment.

Adding these missing details is the subject of this article.

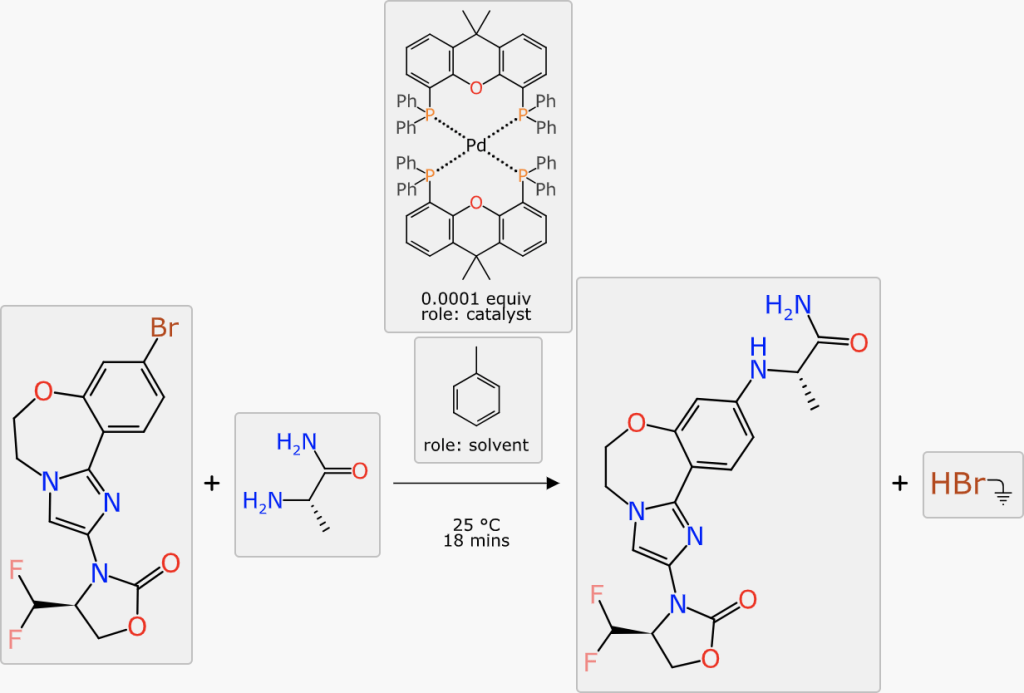

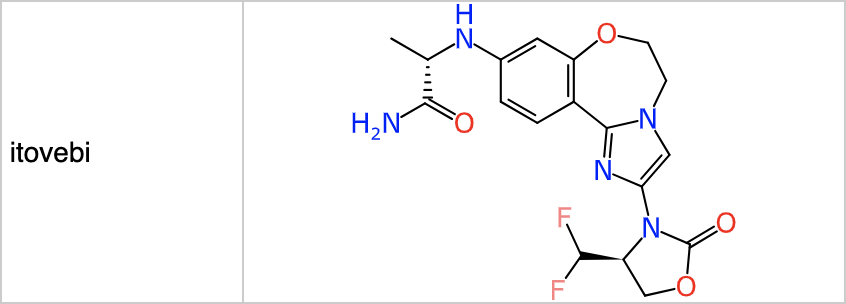

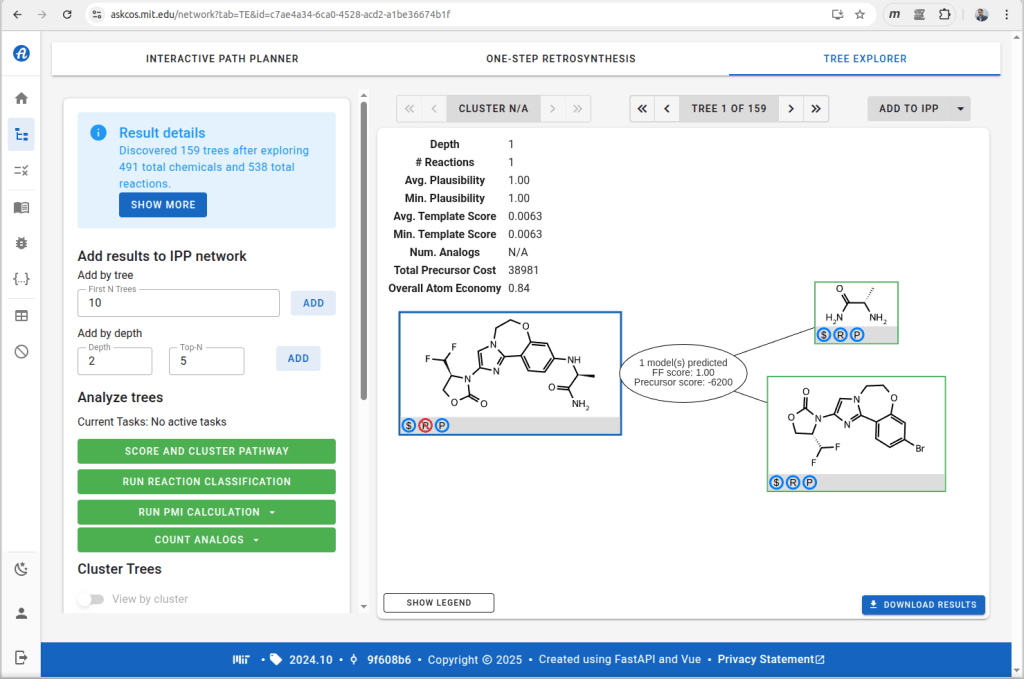

Most synthesis planning tools are commercial products, but one noteworthy exception is ASKCOS from Connor Coley’s group at MIT. The online version can be used with retrosynthetic rules derived from proprietary data, which I highly recommend (try out the rules from text-mined data if you’re curious, and then go back to using the good ones!). Feeding in structures for the FDA approved drugs from the 2024 cohort comes back with plausible suggestions for many of them. For example purposes, I’ve selected the outcome from itovebi:

Feeding this into the reaction planning feature for ASKCOS gives the following result:

Note that the resulting synthesis plan is a single step, so that part is not as exciting as it could be, but this can be blamed no the fact that we have access to massive libraries of commercially available starting materials, and it’s quite likely that the scientists who prepared the drug candidate were using the same ones. For this markup use case, though, we’re looking at one step at a time.

The information generated by ASKCOS is clearly stored internally using SMILES strings, and is functionally equivalent to this ReactionSMILES sequence:

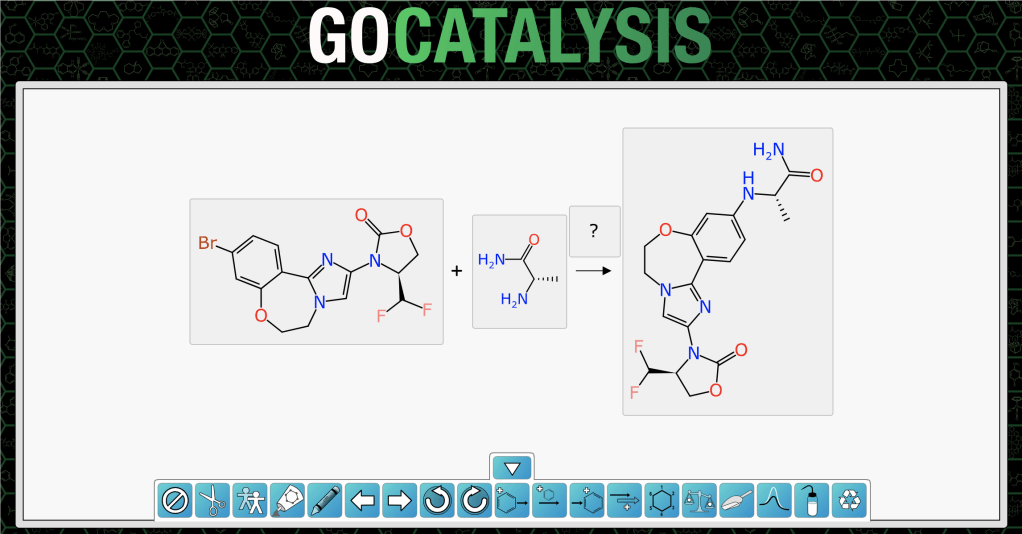

O=C1OC[C@@H](C(F)F)N1c1cn2c(n1)-c1ccc(Br)cc1OCC2.C[C@H](N)C(N)=O>>C[C@H](Nc1ccc2c(c1)OCCn1cc(N3C(=O)OC[C@H]3C(F)F)nc1-2)C(N)=OTaking this string sequence and pasting it directly into the gocatalysis.com site provides this outcome:

The bare bones ReactionSMILES has been unpacked into two reactants and one product, and each of them has been depicted independently, without any of the reaction context, since the atom mapping has yet to be established.

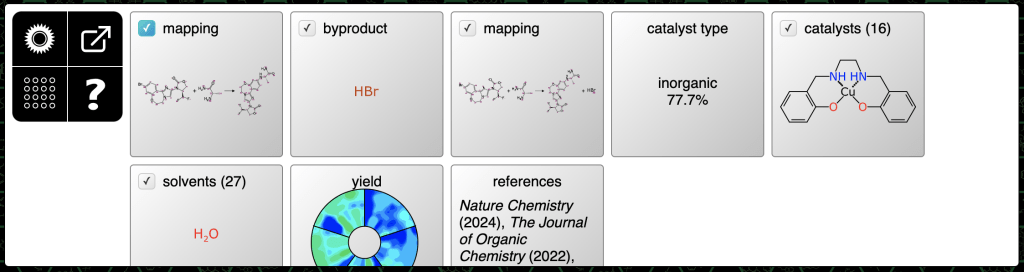

Requesting predictions brings up a series of advice steps:

The first three steps are: (1) mapping for the initially provided components; (2) determination of the formal byproduct; and (3) a followup mapping which includes the byproduct. These can be accepted as-is.

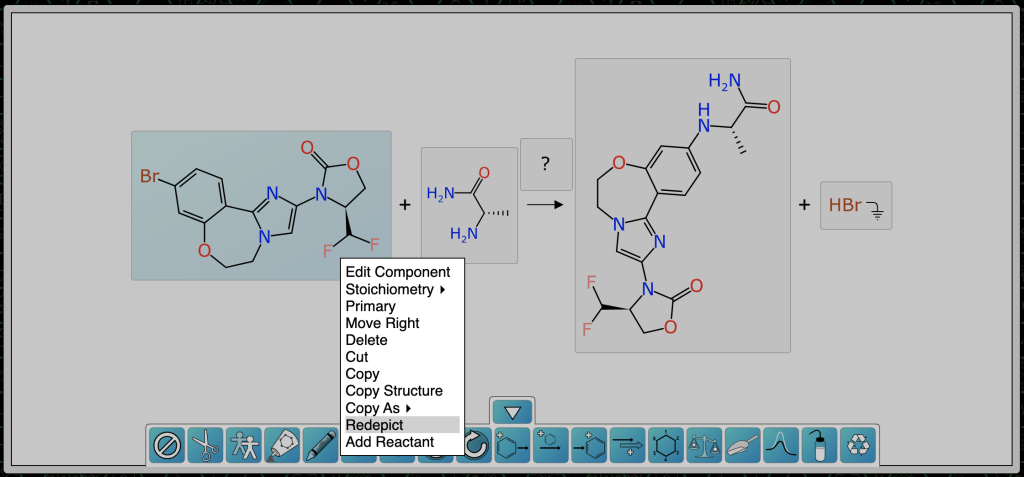

Once atom mapping is done, it is now possible to have the algorithm redraw the components in context – which would have been done automatically if the incoming ReactionSMILES had mapping numbers, but since we assigned them after the fact, we have to ask for it:

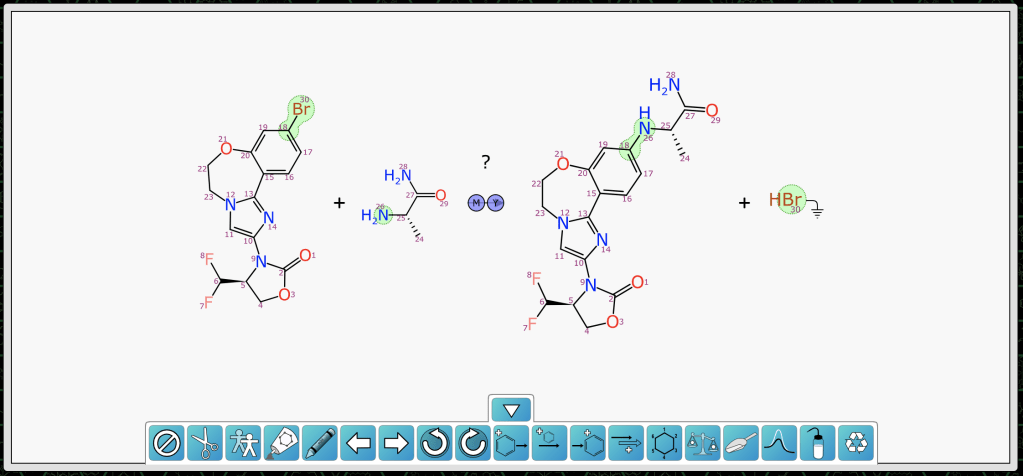

After both reactants have been redrawn, the scheme looks like this, with mapping and transform annotated:

As you can see, the orientation of the bulk of the chemistry is the same, and the smaller reagent has been arranged and aligned so it matches the product. This is more than just a post-depiction alignment, since individual degrees of freedom during the layout process are biased in order to get the preferred result (as described here).

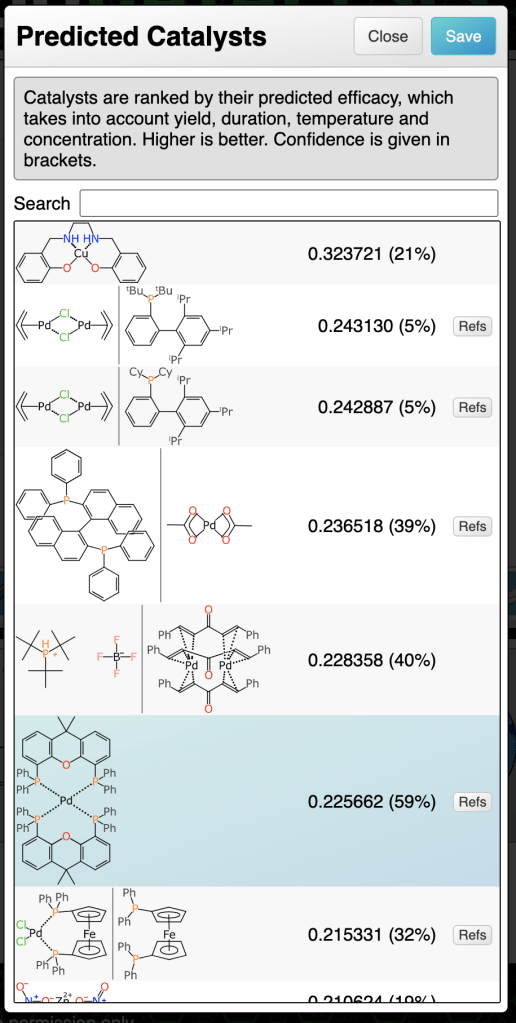

At this point in the markup process, all of the stoichiometric components are present, mapped and aligned ideally. The reaction transform fits into the Buchwald-Hartwig cross coupling category, and this is generally done with a catalyst. The prediction comes up with a number of suggestions:

The catalyst with the highest ranking is a tetradentate copper complex. None of the ranking predictions are high (the operating range is approximately 0 to 10) and it is probably more useful to distinguish the best candidate by confidence: the highlighted palladium phosphine complex has a confidence of 59%, which is a Bayesian-derived indication (see here) that the transform, substituents and catalysts are backed up by a significant amount of training data.

A similar procedure applies to solvents: the highest ranking options are either chlorinated (undesirable) or have a rather low confidence score. Looking further down the list, toluene is an option, and the slightly higher confidence (12%) indicates that there is more training data to back up this choice (note: don’t be tempted to interpret the percentage as the likelihood of it working, it’s an estimation of the reliability of the prediction itself, which in this case will probably be a bit better or a bit worse). Choosing toluene is scientifically reasonable, given the aromaticity and polarity profile of the reactants, products and catalyst (all probably soluble) while encouraging the formal byproduct (HBr) to be somewhere else.

Note that it would be useful to predict the best base for this particular type of reaction, which is not a feature that has been implemented yet, but it is on the radar.

Speaking of radars, the final feature is to select reasonable conditions likely to provide a good yield:

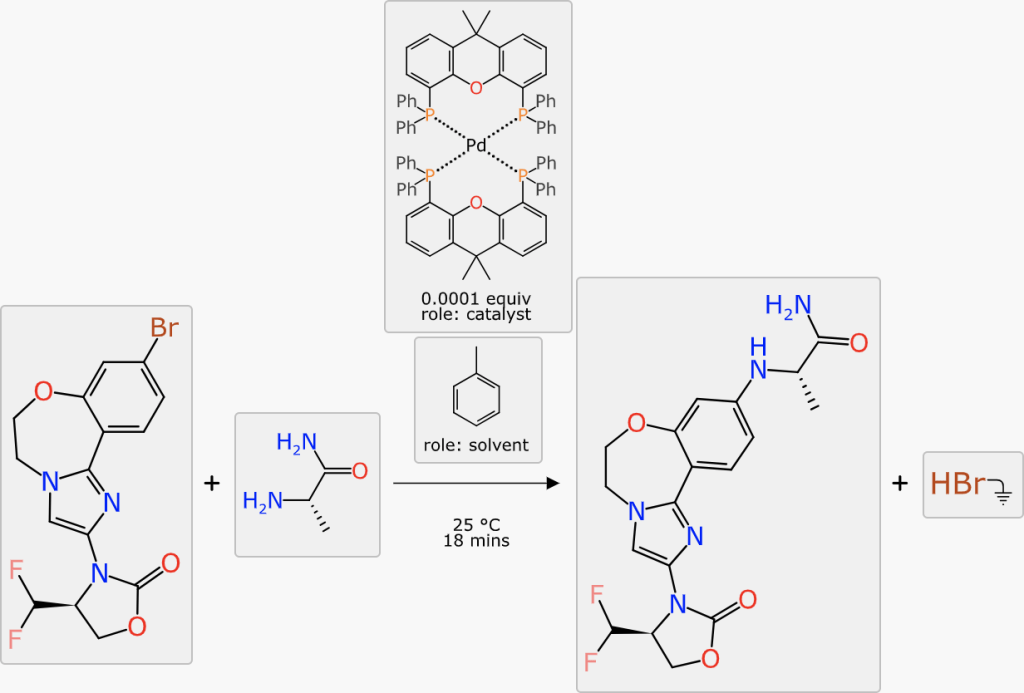

The final scheme markup looks like this, which is fairly close to something you might realistically take to the bench:

The next chapter is about interoperability with ELNs.