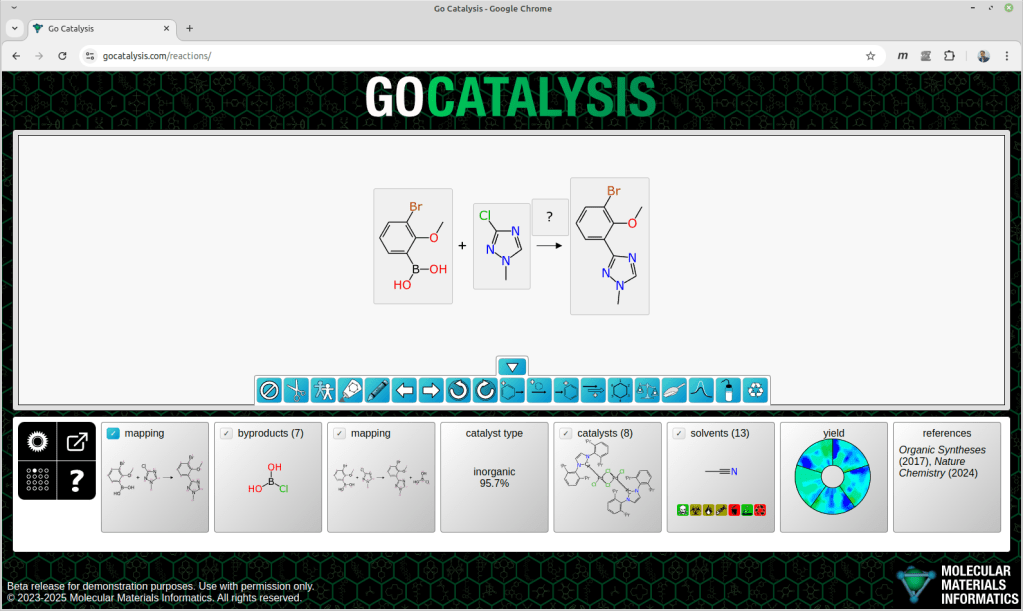

This is the first article in a series about chemical reaction prediction, in particular a work-in-progress site that combines a number of original tools for designing reactions. The general idea is that you start with an incomplete reaction scheme, and the models and algorithms will guide you toward filling out the rest, so you end up with a useful starting point for an actual experiment.

There will be a dozen or so chapters in this series. The following subjects are planned: note that the ones with links are for articles that have been written. They will be retroactively filled in as the content is assembled, so think of this list as a living document.

- Chapter 1: predicting catalysts

- Chapter 2: predicting solvents

- Chapter 3: prediction confidence

- Chapter 4: byproducts, mapping, stoichiometry and roles

- Chapter 5: literature lookup

- Chapter 6: yield contours

- Chapter 7: forward/backward synthesis and reagents

- Chapter 8: aligned depiction

- Chapter 9: component based reaction editing

- Chapter 10: training data

- Chapter 11: exporting graphics

- Chapter 12: synthesis planning markup

- Chapter 13: interoperability with ELNs

- Chapter 14: large language models

What is this and why should I care?

It’s a website. The domain name is gocatalysis.com. It’s called that because my initial locus of attention was catalysis of chemical reactions. The domain name was on sale, so I snapped it up and sat on it for a long time.

The interactive workflow lets you draw or import chemical reactions, and it has a lot of features for recommending what you should add next.

The functionality is powered by a collection of algorithms using an original cheminformatics toolkit that started around 2010. There is a lot going on, and the rest of the series will provide a high level overview. It’s all about molecular structures, chemical reactions, and the software engineering and machine learning technology needed to make these useful. If these subjects are of interest to you, then keep reading. If not, I doubt any of this will come up in a pub quiz, but you never know.

Right now the site is behind a passwall. If these articles convince you that there’s something that you’d like to take a closer look at, there’s only one thing you need to do: send me an email at alex.clark@hey.com, and say hello. That’s about it really – no commitment, just identify yourself as a person, and ideally I’d really appreciate feedback, but that’s up to you.

Zooming out a few levels, the reason why I built a website that makes predictions for chemical reactions is a long story. It goes back to my formative years: my misspent youth involved teaching myself to code when that was barely a thing (long before the internet was called that) and when it came time to embark on the big adventure of university, I wanted to learn about something different. I ended up picking chemistry, and then specialising in the organometallic subdiscipline. As much as I might try to rationalise it otherwise, what it came down to is that I really liked the aesthetics of chemical structures that made up contemporary inorganic chemistry. I was also fascinated by crystallography, of which I got to do plenty during my doctorate, and one of the big differentiators from organic chemistry is that we got to make things that were colourful. I’ll never forget the feeling of satisfaction I got when I decided to synthesise a ligand that had a few more conjugated aromatic groups than usual, and connecting it up to my ruthenium and osmium starting materials produced a deep red-purple solution, which formed crystals that were big enough to mount on the diffractometer. Maybe you had to be there, but that was a good week.

In the late nineties and early 2000’s I spent much effort trying to figure out how to combine software engineering with what I had learned in the laboratory, and back then there weren’t quite so many options. The drug discovery industry was hiring though, so that’s where I went. I sampled almost every corner of computer aided drug design, and ultimately made my home in cheminformatics. Perhaps for the same reasons as previous career choices: chemical diagrams are something I find to be a source of beauty, and that is reflected in the effort that I have put into designing algorithms to get this form of elemental calligraphy as close to perfection as possible, within real world constraints.

Getting closer to the point: being a card-carrying inorganic chemist in the field of cheminformatics has been a stone in my shoe for decades, given that best practices for capturing the informatics of metal-containing molecular entities are still woefully inadequate. As annoying as this is, it is also an opportunity. Where does the study of cheminformatics (which is mostly driven by drug discovery and adjacent uses of organic chemistry) meet inorganic compounds, and need to actually get it right?

Catalysis, of course. Most chemical reactions that use metal catalysts don’t even bother to draw out the structures, and when they do, it’s usually pretty embarassing. So there’s an opportunity to fix that.

Over the course of many years I incrementally improved my chemical reaction drawing tools, to become an effective and ergonomic way of capturing data in an informatics-complete way. By this I mean a reaction scheme in which all of the components are represented by a valid structure: reactants, products, reagents, catalysts, solvents, adjuncts, byproducts. All stoichiometic components fully atom-mapped, everything balanced so that no atoms are left over. Everything sketched out so it’s one click away from being publication ready, with reactants and products aligned to show common orientation. Reaction transforms implied by the atom mapping. Coarse reaction conditions provided (temperature, duration, catalyst concentration, yield). That is the definition of complete that I will be using throughout this series.

I began curating chemical reactions from the literature. It was slow at first: designing a user interface for drawing reactions is harder than it sounds. There are so many opportunities to make it less labour intensive, and to use software to check for mistakes, and building all this functionality takes time. The user interaction is complicated, and it requires high-end algorithms to do things that seem like they should be a lot simpler. My preferred content source was initially method papers for catalyst development. I was not initially certain what I would do with the data, but I had some ideas. It was a back-burner project throughout, with spurts of activity whenever the inspiration hit.

At a certain point the accumulated data resource got large enough to seriously consider doing some model building. I had hand-picked many catalysis-oriented papers, and these have a nice property: the scientists intentionally explore the domain in which a catalyst operates. Naturally they draw attention to reaction conditions where it performs well, but they also explore the boundary cases and show those for which it is mediocre or useless. This is another way of saying that the details of the reactions in my training set describe a lot of structure-activity trends, where structure in this case would be the reaction transform and the molecular composition of the catalyst. Given also that this data is really high quality with very few mistakes, even with just a few thousand datapoints, it ought to be possible to use it to effectively the efficacy of proposed catalysts.

Turns out that it is. Some of the details will be described in the articles that follow.

Most interesting